You Are Not Your Errors – using Learned Optimism to reset.

We’ve all been there: a broken endodontic file, a failed implant, or a crown that doesn’t seat. A disgruntled patient, a collegial dispute or even a legal complaint. As generally Type A people with perfectionistic tendencies, these events can be blown out of proportion and linger on our minds for more time than they deserve. Thoughts start creeping in, keeping us at night as we ponder questions such as:

How did this happen?

What does my patient think of me?

What will my colleagues think of me?

Am I a good enough clinician?

If we’re not careful, unchecked stress and worry, together with mind traps such as catastrophising, black and white thinking, overgeneralisation, tunnel vision and over-identification with work can lead to longer terms problems such as chronic stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction.

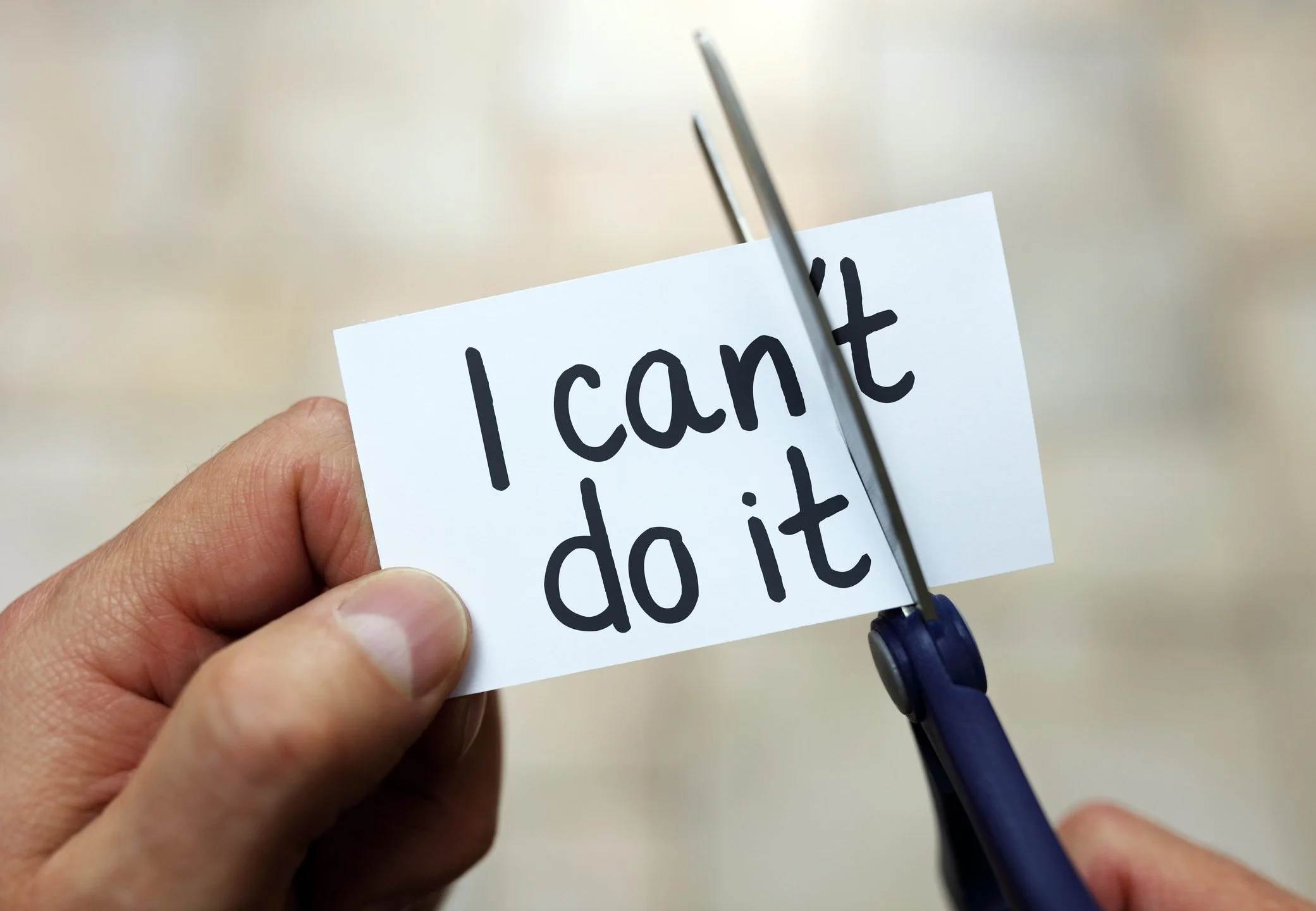

What if there was a way of training our minds to ensure that we’re in charge of our thoughts instead of them being in charge of us? Learned Optimism does just that.

Based on the research around learned helplessness by Martin Seligman in the 1960’s, Learned Optimism is a strategic way of thinking that can be taught and developed in individuals. Most of us would have heard of the terms pessimist and optimist, but the truth is far more nuanced than a fixed label. They are explanatory styles focused on Permanence, Pervasiveness and Personalisation, or the 3P’s. If you have a pessimistic explanatory style, you will view the above scenarios as lasting forever, affecting your whole life and all your fault. If you have an optimistic explanatory style, you will view the above scenarios as temporary and over soon, affecting only a specific part of your life, and due to a range of factors both internal and external.

Learned Optimism focuses on disputing or challenging those thoughts to better serve us, our wellbeing, and our careers. If you find yourself thinking, “This is ruining my whole life”, ask yourself, “Really? Is this event really ruining my whole life or is it just impacting a specific part of my life, my work, my day?”. If you find yourself thinking, “My patient’s going to think I’m incompetent,” ask yourself “Where is the evidence for that? How do I know that’s true?”. If you find yourself thinking, “I should be getting this right”, ask yourself “What’s an alternative way of thinking about this situation?”. If you find yourself thinking, “I’m not a good enough dentist,” ask yourself, “What are the implications on me, my patients and my career if I keep thinking like this?”.

Dentistry is already a challenging and demanding profession, so let’s not make it any harder than it needs to be. Over the next week, see if you can notice what thoughts run through your mind as various events take place and try to dispute them as needed. This may be done more easily as a reflection at the end of the day, but as you become more practised in Learned Optimism, that muscle will become stronger and you’ll find it easier to dispute and challenge your thoughts as they happen, in real-time. So, before your thoughts and feelings take you for a ride you don’t want to be on, nip them in the bud with a pro-active strategy and intentional thinking, in the form of Learned Optimism.

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and freedom”

Viktor Frankl.